Category

PerformanceAbout This Project

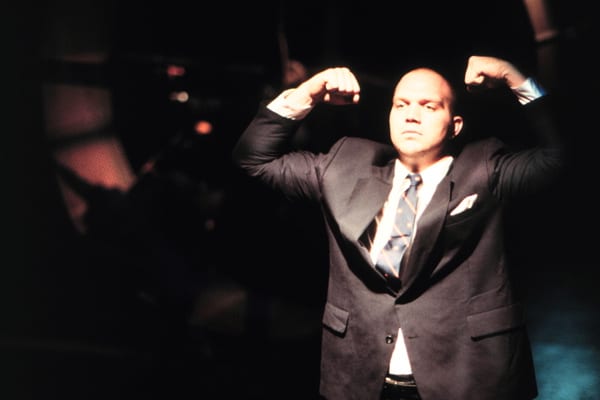

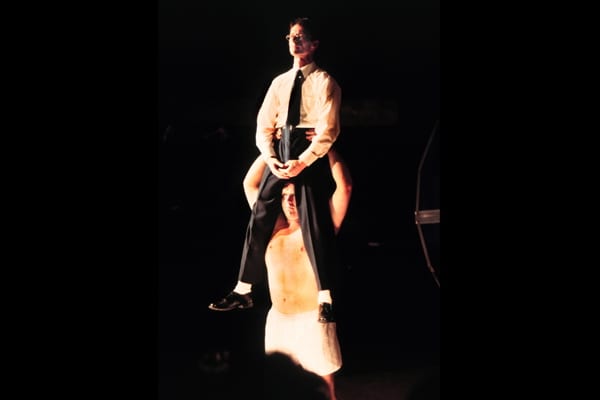

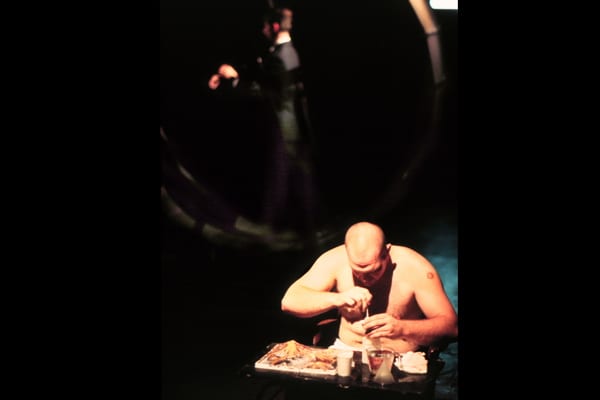

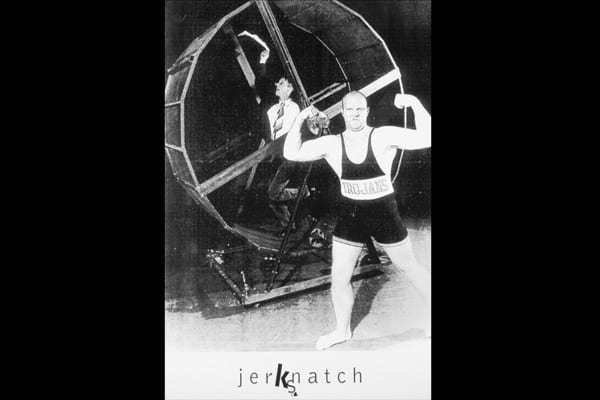

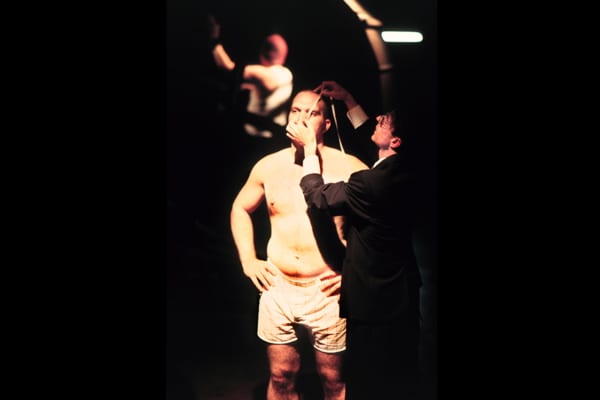

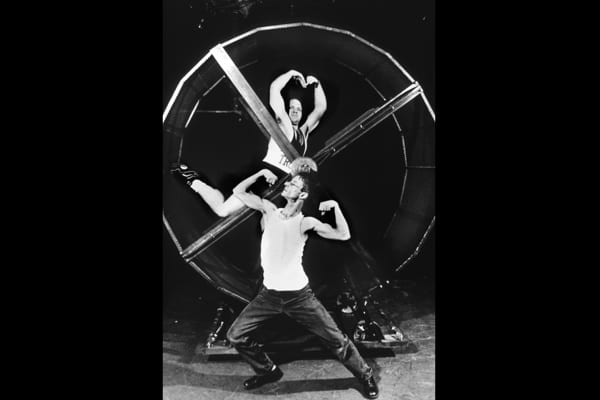

JerkSnatch is a performance portrait of three men (heavy-weight, welter weight, and feather weight) whose environment is a man-sized steel hamster cage, with a running wheel 9 feet tall. These masculine archetypes belly up to the strongest man in the world, tackling confusing and contradictory sets of masculine roles. Three experiments are conducted: a volcano erupts over and over again; silent fireworks are detonated and a crying machine sounds. Sam Shepard’s Repeat text on the (im)/possibilities of remembering personal disasters and being doomed to repeat them forever and ever into eternity figure in the many experiments that take place in the search for “safetyland”.

JerkSnatch combines text, movement and projected images. It draws from diverse references including The Strongest Man in the World, a British play by Barry Collins about a Soviet miner coached to win the gold medal for weightlifting at the Moscow Olympics at great cost to his body and psyche, Arnold Schwartzenegger, The Poor Man’s JAMES BOND by Kurt Saxon, the paintings of Frances Bacon, Edward Muybridge’s photographs and “The Prisoner of War, the lure of gunfire and the enemy within”, by Scott Anderson which appeared in Harpers magazine, January 1997, among other sources.

The jerk and the snatch are two weightlifting moves. Jerksnatchbegan with these considerations: (1) what is an explosion? (2) what becomes an explosion? and (3)safetyland (thanks to a construct suggested by the writing of Matthew Ghoulish). The program notes for the performance include this text: “There were four times in my life that I saw my father cry. I received a kit of experiments from him for Christmas when I was 8 years old. I was only supposed to play with them when he was around and could do them with me. As was the case with most dads of that generation, he was always working and wasn’t around much. Bored and inquisitive and with little patience for waiting, I conducted the experiments in secret and would erase the markings and carefully re-wrap all the tools so he wouldn’t know, but of course he discovered my crude cover-up. And when he did, he cried. This was the first time. The second time I was 16 years old and he found me in bed with my boyfriend. The third time he was teaching all of us kids to shoot, my dad was a hunter, and we were skeet shooting in northern Wisconsin. He was following the skeet over a bank of trees and the bullet rang out and clipped a seagull passing by. He ran and made us run all over the woods until he himself found the dead bird. He knelt down, picked it up and wept. The last time I was in my early twenties and we were bitterly arguing over Nixon. My father was a Chicago Democrat, an amalgam of working-class union man and loyal-to-authority-no-matter-how-rotten Republican, and he had voted for Nixon. He couldn’t stop defending him until long after Watergate had become the spectacle of our time. He finally broke and choked out, “He was nothing but a crook, a common crook.” This performance is dedicated to my father, Clyde Owen Wilber, 1924-1994

Photos © Dan Rest